Poynterville: Origins of a black community

Published 8:11 pm Saturday, November 26, 2016

Following the Civil War, in December 1865, ratification of the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States. Free blacks would experience difficult times in post-war Clark County.

The majority of men worked for wages as farm laborers, the women in domestic service, and most families lived in extreme poverty. Enterprising individuals and those with a skilled trade fared better than others, and a few were able to acquire property in one of the black communities that sprang up in Clark County — Lisletown, Hootentown, Poynterville and others.

Poynterville has a long and interesting history. In this article, however, we only have space to explore its formative years, beginning with the man who gave the community its name.

Wiley Taul Poynter (1838-1896) was born in Montgomery County, grew up near Frankfort and came to Winchester while still young. At age 17, he was the principal and a teacher at the Winchester Academy. He married Pattie Poston in 1857. Poynter served with the Union army during the Civil War as regimental quartermaster for the 16th Kentucky Infantry. Returning to Winchester, he worked as a bookkeeper for his father-in-law, Henry Poston, and in 1865 became the first cashier of the Clark County National Bank.

According to his biography, Poynter, an ardent Methodist, entered the ministry in 1867 and “at once took front rank.” He pastored the church in Winchester for four years, then preached at Millersburg and Paris. In 1879, he purchased the Science Hill Female College in Shelbyville. The school had been established in 1825 by Clark County native Julia Ann Tevis. The Rev. Poynter hired 16 well-qualified faculty members to teach 125 or so students and achieved a national reputation for the school. The school closed in 1939, and the buildings are now occupied by the Wakefield-Scearce Galleries.

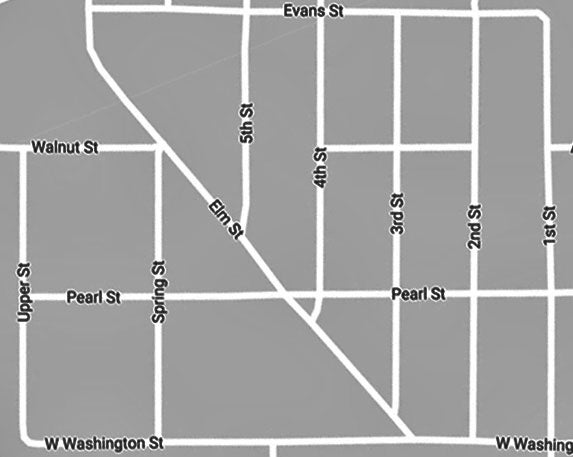

Bringing our story back to Winchester, we find from deed records that Poynter purchased 65 acres of land adjoining the west side of Winchester from William H. Winn. In July 1867, Poynter had the tract laid out in 52 lots and platted as “Poynterville.” The new subdivision was bordered on the north by Walnut Street, on the east by First Street, on the south by an extension of Washington Street, and on the west by Elm Street, which was then called “the old Paris Road.” Poynterville was the first of many suburbs created in Winchester’s history.

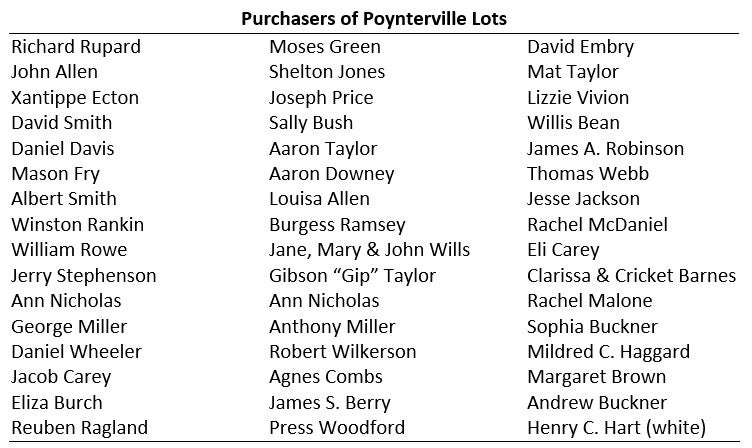

Wiley Poynter left behind no explanation of his purpose for creating Poynterville but after examining his lot sales, his intentions seem clear. From July 1867 through the end of the year, he sold 19 lots, all to African Americans. He continued the practice after leaving Winchester. Between 1867 and 1890, he made 54 deeds conferring 66 lots in Poynterville; all the sales but one were to African-American men or women whose names are shown in the table to the right.

The lots sold exceeded the number laid out in the plat. Some of the sales were for “half lots.” Poynter also sold some of the lots on credit — an unusual practice for selling to blacks at that time—and a few of the purchasers lost their lots by not paying the full amount.

Poynter must have intended his suburb to become a community for black families. This notion is supported by his article, “The Church and the Black Man,” published in the Methodist Review, which begins, “I risk nothing in saying that among the imperative and pressing duties of the American Church, and especially of the Church in the Southern States, none is more important than the duty to the colored people in our midst.” He stated that “the home, the school and the Church” were critical factors, and that first they “must be housed in homes of their own…. There can be no true progress without this.”

Few of the purchasers of lots in Poynterville had an occupation other than farm laborer. John Allen was a house painter, Mason Fry a distillery worker, Jerry Stephenson a grocer, George Miller a butcher, Aaron Taylor a post and railer (fence builder), Gip Taylor a railroad worker, Samuel Brown (husband of Margaret) a harness maker, and Thomas Webb a blacksmith. Laborers who purchased lots must have carefully saved their wages.

At least six of the buyers were Civil War veterans (Mason Fry, Joseph Price, Reuben Ragland, Burgess Ramsey, Gip Taylor, Thomas Webb), who could have used their military pay to buy lots.

Thirteen of the buyers were women; their reported occupations were housekeeping and domestic service.

John Allen, Reuben Ragland and Shelton Jones were trustees of the CME Church on Broadway. This was the first black church in Winchester.

Thirteen of the lot owners had been married while enslaved: John and Louisa Allen, Aaron and Catherine Downey, David and Milly Embry, Moses and Anna Green, Shelton and Mary Ann Jones, Anthony and Joan Miller, George and Betty Miller, Joe and Mary Hannah Price, Reuben and Nancy Ragland, Richard and Nancy Ragland, Jerry and Kate Stephenson, Aaron and Mandy Taylor, Gip and Manda Taylor. Their unions were not legally recognized before the Civil War. After the law was changed, black couples paid scarce money to formalize their marriage ties.

Eliza Burch purchased a lot in 1869; she died in 1876. By will, she left her house and lot in Poynterville to her son, Samuel, who “has for the last four years cared for me during my sickness”; it was to be “compensation for his kind treatment of me and his loving care and protection.” She could leave sons Philip and Ames only “a mother’s affection.” She added, “My other children were sold during slavery and I do not now know whether they are still living or not. I can only leave for them a mother’s prayer that they meet me in heaven.”

More research needs to be done to gather information about the first men and women of Poynterville.

One year after Poynterville was laid out, the heirs of John Bruner established an adjoining suburb: Brunerville (1868). Brunerville lay on the west side of Elm Street and was framed by Walnut, Upper and Washington. Brunerville persisted until sometime in the 20th century, after which the area was assumed to be part of Poynterville.