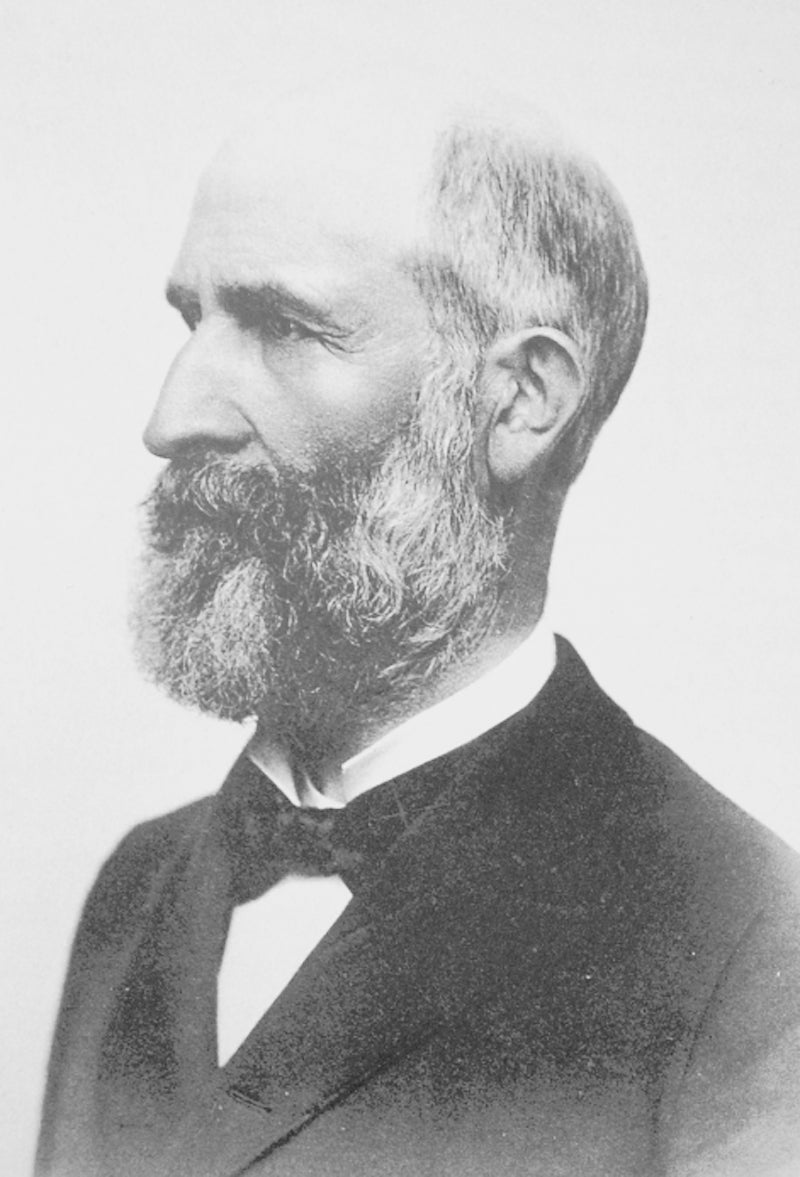

William M. Beckner: The ‘Horace Mann of Kentucky’

Published 10:22 am Friday, October 27, 2017

By Harry Enoch

William Morgan Beckner (1841-1910) earned a glowing obituary in the newspaper he founded.

“He advocated for better schools, better roads, better streets, turnpikes and railroads, and public improvements of all kinds. He was not afraid of increased taxation if the community secured corresponding benefits. He was largely responsible for the removal of Kentucky Wesleyan College to this city. Much of the most progressive school legislation of the State was due to his influence. He was also a great advocate of increased rights and privileges of women.”

Beckner followed his beliefs with action.

“Judge Beckner was by nature a leader of men. What he believed was right he advocated with all his might whether or not it was popular at the time.”

This was especially true regarding the issue of public education. Here, Beckner left his most enduring mark, and the principles he fought for are still relevant in Kentucky today.

You may recall Kentucky’s education crisis that resulted in a 1985 lawsuit, Council for Better Education et al. v. Martha Layne Collins, Governor, et al. Former governor Bert Combs and his legal team argued that the poorer counties of Kentucky could not provide an adequate education for their children due to an insufficient local tax base compared to wealthier counties.

Statements such as “48 percent in this county can’t even read” were undisputed by the defense. Judge Ray Corns heard the case and his opinion declared Kentucky’s entire system of school finance unconstitutional.

The General Assembly immediately appealed to the Kentucky Supreme Court. That court’s final opinion issued in 1989 found “the system of common school education in Kentucky to be unconstitutional.” The state’s widely publicized Education Reform Act of 1990 (known as KERA) was the result of the court’s sweeping mandate.

So what does the Kentucky constitution say about education? Section 183 requires that “The General Assembly shall, by appropriate legislation, provide for an efficient system of common schools throughout the State.” Both courts cited this clause as the basis for throwing out the existing education framework. And this clause was the work of William M. Beckner, Clark County’s representative to the Constitutional Convention of 1890.

Beckner was born in Moorefield, Nicholas County, and attended neighborhood schools, the Richeson and Rand Academy in Maysville, and Centre College.

Leaving college after five months because of a lack of funds, he taught school while reading law in Maysville.

Beckner settled in Winchester in 1865, where he began his law practice, and was soon elected police judge. He also served as principal of Winchester public schools and was founder and editor of the Clark County Democrat.

In 1866 he was county attorney, four years later county judge, in 1880 state prison commissioner, and in 1882 state railroad commissioner.

In 1893 he served in the General Assembly and a year later was elected to fill a vacancy in the U.S. House of Representatives occasioned by the death of Marcus C. Lisle.

Beckner’s passionate belief in the value of education led to his effort to reform the state’s system of common schools.

Kentucky, like most of the rural South, had a deplorable record of educating its citizens. Our first state law dealing with common schools was not passed until 1838 — and compliance was voluntary.

Slight progress was made in the 1840s and 50s with enactment of a small state school tax. The Civil War disrupted progress, as did hostility to local taxation, political infighting, racial tensions and citizen apathy.

In the 1870s, Beckner began advocating for better education in his newspaper columns and eventually was able to secure passage in the legislature of a graded public school system in Winchester.

Following this, he began speaking out around the Commonwealth on the need for more state funding of schools. Condemning the level of illiteracy, he argued that “the free school has been the foundation of New England’s power and greatness.”

He urged citizens to raise local taxes and to provide adequate education for black children — at that time the state had grossly unequal school systems for white and black children.

One of his speeches, entitled “A Problem To Be Solved,” was reprinted in newspapers across the state in 1882.

He organized a state Education Convention in Frankfort in April 1883 and the Inter-State Educational Convention in Louisville that September.

These efforts resulted in Kentucky’s Common School Act of 1884 that created a “uniform system of schools” but did nothing to address their inadequate funding.

In 1889 he was invited to speak at a symposium in New York City on the question, “Shall the Negro Be Educated or Suppressed?” There Beckner expressed “a Christian hope that prejudices of the past would die, racial antagonism cease, and equal rights before the law endure of “all races of men.’”

Elected to represent Clark County at the 1890 Constitutional Convention, Beckner was easily the most widely recognized advocate of public education.

He worked tirelessly during the 226-day convention to advance his ideas in the Committee on Education.

When the convention took up debate on the committee’s report, Beckner asked if he might “say a word or two.”

He then launched into a two-hour oration that touted education’s “power to break down class barriers, prevent crime and poverty, enrich democracy, and improve the general economic condition of the state.”

The convention ultimately voted to approve his committee’s six sections on education. For his efforts he was recognized by the other delegates as the leader of the “friends of education” and dubbed “the Horace Mann of Kentucky.”

Beckner had no way of foretelling that 100 years later, his Section 183 would be the justification to remake Kentucky’s education system.

Harry Enoch, retired biochemist and history enthusiast, has been writing for the Sun since 2005.