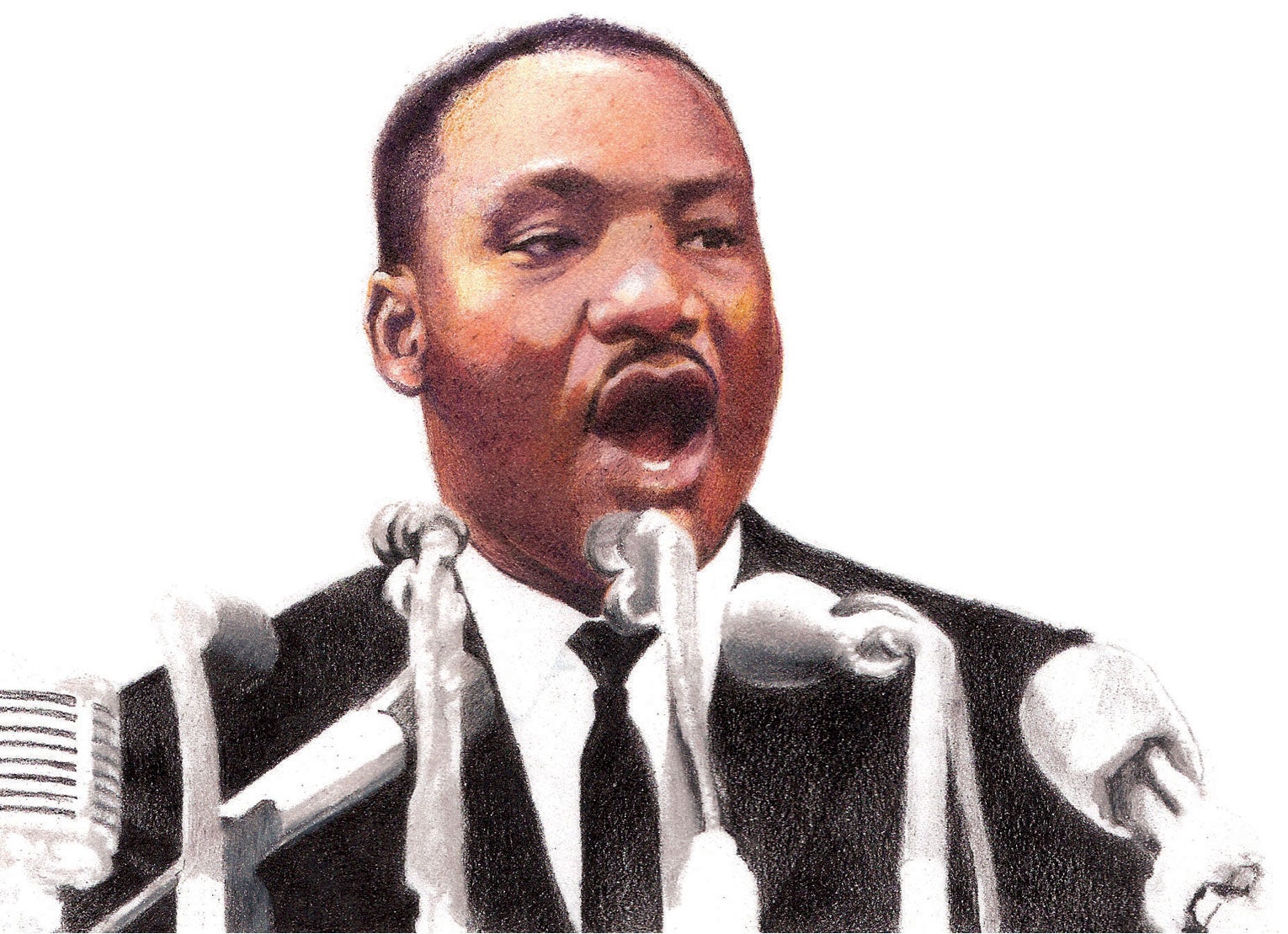

Legacy alive: 50 years after his death, Clark residents talk about how MLK’s life inspired theirs

Published 10:59 am Wednesday, April 4, 2018

There are particular events in history during which it feels time stands still, if even momentarily.

These are moments that will be remembered for lifetimes.

For many Americans, the news of the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., perhaps the most renowned civil rights leader in history, marks such an occasion.

Many can still remember where they were the moment they learned King had been assassinated April 4, 1968, in Memphis.

‘Violence accompanied grief’

The news of King’s death sent a wave of shock across the globe. Many were left mourning the loss of the man who had led the civil rights movement since the mid-1950s.

Others were outraged, and riots erupted in major cities, with dozens of deaths, multiple injuries and hundreds of arrests reported.

The top headline from the April 5, 1968, edition of The Winchester Sun was, “Violence follows news of King’s assassination.”

“The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. triggered … violence across the nation,” the Associated Press story read. “The president called a late morning meeting of civil rights leaders in the White House in the convulsion wave of reaction following the death Thursday night of the 39-year-old King.”

King died in a Memphis hospital less than an hour after he was shot in the neck as he stood on the balcony of his hotel there.

“Police searched for a white gunman,” the story continued.

But, the violence was also met with grief.

“The violence that swept some streets accompanied the national outpouring of grief and sorrow that followed the death of King, the nation’s leading advocate of nonviolence and a Nobel Prize winner.”

Such was the case in Kentucky, where Joyce Morton sat weeping as she watched the news coverage of King’s death from the dorm hall where she lived on the campus of Morehead State University.

A sophomore in college at the time of King’s death, Morton said she can still recall the sorrow that swept over her and her classmates that day.

“I remember that day,” she said. “Our dorm lady came to let everyone know what happened. We all just gathered around the TV and cried.”

‘I believed him’

Just four years earlier, Morton was one of hundreds who gathered in Frankfort for one of King’s marches.

Morton was a sophomore at George Rogers Clark High School when she learned King would be visiting Kentucky. Although she and her peers were advised by school administration not to attend the march, Morton felt she had to go.

“We were told we would not be excused for the day,” Morton remembered. “They told us we would get zeros in all our classes for the day.”

But, Morton begged her mother to be allowed to take a bus with NAACP representatives to the march.

“I told her, ‘Please let me go. I don’t care if it’s not excused. This is something I believe in,’” Morton said. “And she let me go.”

For Morton, attending the march was important because she believed in King’s message of equality.

Although she attended high school when GRC had been integrated, Morton said she still felt like an outsider.

“I wanted to take part because I was a part of the segregated school at Oliver, and when we were moved to GRC, I did not feel welcome,” she said. “I remember at that time being called coons, being called names and being told they did not want us there.”

Morton said she and her African-American peers felt like guests in the Promised Land.

“We were told we were welcome, that integration in our schools was the Promised Land,” she said. “But we didn’t feel welcomed. We felt like guests. So, I wanted to go to MLK’s march because I felt I could make a difference.”

Morton recalls the emotions she felt listening to King speak.

“You believed what he said,” she said. “That we were all Americans. That I had a right to an education, to live where I wanted, to attend school where I wanted. I believed his speech when he said that we were all there, marching together, for the good of all.

“And I still think about that.”

‘It was a sad day’

While Morton was watching the reverberation of King’s death play out at MSU, Deatra Newell sat quietly in the halls of Oliver Street School watching it play out in Winchester.

Newell was 8 years old. She recalls standing in the halls watching the news coverage of King’s death on the TV.

“I was finishing my last year at Oliver school,” she said. “It was still segregated at the time. We didn’t quite understand the significance of MLK at the time, at that young age.”

But Newell was old enough to understand the atmosphere.

“It was a very sad day,” she said. “I was very quiet and calm. We knew something terrible had happened. Our teachers didn’t really show their emotions that day. But they did make sure that we were informed.”

Newell said she was a teenager when her father, Chester Garrard, started really talking to her about King’s legacy. He was a founding member of the Winchester Unity Committee, which plans an annual Unity Celebration on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Along with Dr. Elaine Farris, Alvin Farris, Marie Gainey, and others, Garrard helped plan a march and a breakfast in King’s honor.

“I participated because my father was and I did what he did,” she said. “We had to do it, but as a I got older, it became important to me, too.”

Newell now heads up the committee that continues the tradition and is an equal rights activist herself.

Newell said she doesn’t recall learning about King in school. But as an adult, she learned more about his “I Have A Dream Speech,” and was deeply inspired.

“What sticks out to me most is that he wanted unity and fairness for everyone,” she said. “He wanted equality for black, white, yellow, everyone. He wanted a world where all children would come together to be free at last. And he desired a world where people would be judged by the content of their character rather than the color of their skin.”

And Newell still dreams of that world, she said.

“My parents always taught me those lessons,” she said.

‘His dream had died’

However, after King’s death, many in the African-American community felt that dream had been lost.

“I felt discouraged after his death,” Morton said. “I felt that his dream had died. This man that was leading us in a Godly manner, that hope for a brighter future, it was gone.”

Morton recalled many church gatherings in the wake of King’s death, where people were able to mourn together and share their feelings about the great loss.

Newell said her parents stayed glued to the TV for days.

“They were sad and quite taken aback,” she said. “There was this feeling that we finally had someone to lead and try to make a difference for them and their children, and now he was gone.”

‘It’s a heart problem’

Newell said she didn’t know much about Jim Crow or the term racism growing up, but she did recall experiences with it.

The woman said she will always remember the feelings of fear she felt one day when she accompanied her father to pay a parking ticket.

“I hadn’t been in town a lot,” she said. “I hadn’t been around many white people. I was scared because I hadn’t been in that environment. I sat in my dad’s truck afraid that he may not come back. That they might put him jail for that parking ticket.”

Newell said she attributes much of the issues with prejudice and racism to fear of the unknown.

“When our schools were integrated, I went to Fannie Bush and I had all white teachers, maybe 20 black students there,” she said. “I had a roommate in college who was from Chicago and told me she was scared of black people. But what she didn’t realize was that black children were afraid of white people, too. White children were told stories about black people that made them scared. But what we knew of white people was slavery and the stories of parents being taken, beaten, forced to work.”

She said generations of people may not realize that much of the issues with racial discourse fall back on myths, misunderstandings and fear.

“People in their 60s or older, they may not realize that people of different races still have fear in their hearts today,” she said.

Morton agreed the issues fall back on the heart.

“You know, things haven’t changed much over the 50 years since King’s death,” she said. “Because the hearts haven’t changed. We’re still fighting racism. And if it’s not about race, it’s about class or it’s about religion. It’s the hearts that need to change. There are enough rules on the books to change things, but until the heart changes, we will continue to be in this state.”

Newell said she believes racism is still an issue. She weeps over the shootings of black men, and she still sees a need to fight for equality for all, regardless of race or class.

“There is a whole section of town that I feel does not get equal representation because they are lower-income,” she said. “There is still a great need for us to fight for unity and equal representation. Even our local government needs to do a better job.”

‘Straighten your back up’

Newell said she sees King’s dream live on in the wake of current events.

“I see these children marching in the streets, demanding change,” she said. “I see teachers protesting. And I see people of all colors doing it together. I see children of all colors protesting peacefully. And that generation is not going away.”

A Baptist minister, King’s message of equality was steeped in his desire for nonviolent protest.

“From his demonstration of nonviolence and peace to get something accomplished, I think that has had an effect on everyone. That’s what he wanted,” Newell said. “It taught me that you advocate for the less fortunate and be a voice for the unheard. He set the stage for it to be done peacefully and still get done what you want.”

Newell said she also learned that change does not come overnight.

“It’s a process,” she said. “That’s something I still have to learn at 58 years old. It’s a process.”

However, she lets King’s words be her motivation to stand.

“He said whenever men and women straighten their backs up, they’re going somewhere. So, if you want something, straighten your back up. Stand.”