‘We cannot give up’ | Local agencies continue fight against the fatal drug epidemic

Published 1:47 pm Monday, May 7, 2018

Winchester EMS personnel went about five days before responding to their first overdose call of 2018.

That is according to the Sun’s public records.

Jan. 10, there was another call of an overdose, according to the Sun’s public records. The following weekend, there were two more calls and so on and so on.

In total, EMS personnel have responded to at least 47 calls classified as an overdose since the start of the year.

Between January and April 2017, EMS responded to at least 35 calls.

So far this year, there was just one week — Mar. 25 through Mar. 31 — where there wasn’t at least one EMS call regarding an overdose, according to the Sun’s public records.

In 2017, EMS personnel or police responded to at least 125 calls classified as an overdose.

Though, these numbers may be much more.

Live in Clark County? You’re more likely to die from a drug overdose.

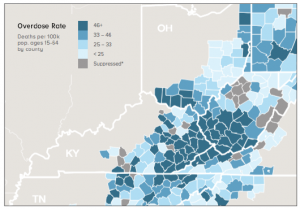

The Appalachian Regional Commission and NORC at the University of Chicago recently released a new data tool which has information on drug-overdose death rates for each county in the sprawling region.

Residents throughout Appalachia — including Clark County — are 55 percent more likely to die from a drug overdose than people in the rest of the United States, she said.

The Appalachian Overdose Mapping Tool illustrates the relationship in each Appalachian county between overdose deaths and socio-economic factors, including poverty, unemployment, education, and disability.

The Appalachian Overdose Mapping Tool, which can be found at overdosemappingtool.norc.org, reveals that residents of the Appalachian Region, which includes Eastern Kentucky counties, like Clark, are more likely to die of an overdose than other regions of the country.

Wendy Wasserman, ARC director of communications and media relations, said the results were grim, but having the data and visualization tool could help communities.

“To have a visualization of how these premature deaths are relating to other socio-economic factors will help community members find a possible point for intervention,” she said.

Appalachia includes all of West Virginia and parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia.

The tool lists Clark County as having a 52.3 overdose mortality rate for 2011-15, according to the map which looked at deaths per 100,000 residents between the ages of 15-64. That is up five points from the 47.3 overdose mortality rate between 2006-10.

The drug overdose mortality rate for the entire region jumped nearly seven points while the mortality rate for the U.S. in its entirety climbed 3.3 points.

Areas with the highest overdose mortality rate are of a white majority with a massive population of people being between the ages of 15 and 64.

These counties also have at least 10 percent or more of the residents listed as disabled, citizens typically make less than $40,000 a year, at least 15 percent or more of the population is considered to be living in poverty, and there are pockets of high unemployment. However, Clark County has a relatively low unemployment rate in comparison, according to the tool.

In Central Appalachia — which includes Clark County — counties with the highest rates of overdose are often the same counties with the greatest percentages of people on disability and the lowest rates of educational attainment, according to a release.

Clark County’s median household income went up $1,384, and both the unemployment rate and poverty rate decreased — a 16 percent poverty rate from 2006-2010 dropped to 15.4 percent during 2011-2015, and an 8.3 percent unemployment rate dropped to 7.9 percent, according to the data.

Despite Clark County’s slight economic growth, the drug overdose mortality rate continues to increase.

Wasserman said the data doesn’t account for the change in potency in drugs over the years. Heroin and other opioids have become more potent and more deadly each year. For Clark County, while economics might have improved so might have the potency of drugs distributed throughout the community.

Wasserman said the data also doesn’t account for new drugs hitting the market, such as fentanyl coming into circulation in 2015.

A more holistic look at drug risks and fatalities.

Kentucky overdose fatalities continued to increase in 2016, according to a report from the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy.

Opioids are the leading cause of overdose deaths. Risks are higher with a history of drug misuse, substance use disorder, previous overdoses, mental health conditions, sleep apnea, older age and pregnancy.

A review of cases autopsied by the Kentucky Medical Examiner’s Office and toxicology reports submitted by coroners indicates that in 2016, morphine was the most detected controlled substance in overdose deaths, present in approximately 45 percent of all cases. When metabolized, heroin reveals as morphine in toxicology results.

Examiners detected fentanyl in about 47 percent of cases; and heroin in 34 percent.

Between 2012 and 2016, there were approximately 58 total overdose deaths in Clark County according to the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy 2016 report. These deaths represent both intentional and unintentional overdoses by illicit and prescription drugs.

Opioid overdoses are one reason US life expectancy declined for the first time in decades. Life expectancy was improving until the opioid epidemic scourged households across the nation, according to the National Vital Statistics Systems.

Wasserman said the mapping tool and other data helps dig a bit deeper into understanding the extent of the opioid crisis, but there’s still more work that researchers could do. It is worth asking, she said, if overdose mortality rates are higher where educational attainment is lower, should there be a comprehensive push for access to education?

“I think it’s a great way to look at overdose in a more holistic context,” she said. “Data doesn’t capture everything, but it should help people with these efforts.”

Overdose is imminent.

Heroin on the east coast is easy to lace with fentanyl and carfentanil. Amber Fields, a peer support specialist with Achieving Recovery Together in Winchester, said it is easier to charge more for the product while also having potent heroin.

Fentanyl is a fast-acting narcotic analgesic and sedative that addicts abuse for its heroin-like effect. Carfentanil is 100 times more potent than the same amount of fentanyl and 5,000 times as potent as a unit of heroin. Anti-anxiety drugs such as Xanax and Valium can also lead to overdose as well, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“The problem with this is it’s making overdoses much more prevalent across the East Coast,” Fields said. “Winchester has seen a surge of overdoses and overdose deaths in the last few years.”

Fields said downtown businesses are dealing with drug use and overdoses in close proximity; Hepatitis C is ravaging communities because of intravenous drug use and needle sharing and drug users often progress from a legal prescription of pain pills to heroin because of addiction’s fatal grip.

“Once the prescription runs out and the person finds the need for more, they move to the streets to find the drug,” she said. “After a while, they come to the realization you get a quicker high from injecting the drugs, and it saves you money.”

Heroin is cheaper, stronger and more deadly.

“An individual doesn’t know when buying heroin what is laced with fentanyl, what is laced with carfentanil, or what isn’t laced at all,” Fields said. “They have no idea of the potency.”

That means someone could get heroin from one person, and it doesn’t do much. The same person buys it from someone else, does the same amount and overdoses.

“Your body shuts down,” Fields said. “If nobody finds you and administers Narcan, you die.”

Another risk for overdose is relapsing. Often, an individual is sober for 90 days, and something happens to make them want to use, she said. They use same amount of heroin they shot before they were sober, and they overdose, Fields said.

“Overdose is pretty imminent.”

Save a Life 101

Fields said ART is working to make it less so.

ART established the Overdose Intervention Task Force in partnership with Clark Regional Medical Center.

When CRMC sees an overdose patient, it will notify a peer support specialist at ART.

Peer support specialists will be in the emergency room within at least 30 minutes of the overdose.

Fields said peer support specialists would discuss recovery options with the client, give them Narcan to take home and talk to them about the local needle exchange and safe use practices.

“Hopefully, this will help us to gain a better understanding of target groups/ages/drugs causing overdoses,” Fields said. “This data will allow us to hopefully find a better solution to the overdose problem.”

Ron Kibbey, a board member on the Clark County ASAP (Agency for Substance Abuse Policy) board, said ASAP has monthly meetings and also hosts overdose prevention seminars throughout the year to educate the community and train citizens how to use naloxone, also known as Narcan, an opioid overdose reversal drug.

Those who take part in the training take home two doses of Narcan, which they can then safely administer to someone having an overdose. Narcan comes in the form of a nasal spray designed to stabilize a patient so additional medical help can be given.

Kibbey said ASAP makes citizens aware of the Good Samaritan law in place to protect people who might otherwise not call 911 because of fear of getting in trouble.

In September 2016, the Clark County Board of Education voted 4-1 to allow George Rogers Clark High School and Phoenix Academy to store Narcan, making it readily available in the event of an overdose on school property. As of last year, the school hasn’t had to use its Narcan doses since the board’s approval, according to a previous article in the Sun.

Access to Narcan often makes the difference between life and death for a person having the overdose. It is not addictive, and only takes a couple of minutes to take effect, blocking opioid receptors for about 30 to 90 minutes.

The Winchester Police Department and the Clark County Sheriff’s Department require their officers and deputies to carry Narcan on the job.

Community organizers expressed the importance of having naloxone and knowing what to do in the case of someone overdosing such as putting someone in the recovery position, performing rescue breathing and most critically, calling 911.

Ripple effect

If you throw a rock into a pond, there’s a big splash. But if you look closely enough, you’ll see from that big splash a ripple effect expanding across the whole pond.

“That’s what we do,” Kibbey said.

Kibbey said ASAP is already saving lives through the community education efforts.

“About three weeks after the first training, I had a lady that I know come up to me,” Kibbey said. “She was interested in finding out more, and she had a neighbor that had a daughter that was using, and so she wanted to learn more, but she went home that night with Narcan. Probably about a week or so after the training, she got a call from her neighbor in the middle the night, it was frantic and she thought her daughter overdosed, and so she was able to go to the neighbor’s house and administer the Narcan and save that girl’s life.”

Kibbey said even if he never heard another story like that, he knows ASAP made a difference.

But since then, he’s heard dozens.

“If we can save a person’s life that gives them an opportunity,” he said. “Number one: to continue to live, but it also gives, hopefully, an opportunity for them to decide to change their life. Some people do some people don’t. But for those who do it has a ripple effect on everyone around them, the family and the community at large.”

Not enough

Most people who meet the definition of a drug use disorder don’t get treatment, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

“My biggest concern with this issue is that we do not have enough treatment options,” Kibbey said.

Most crimes in Clark County are drug-related, Kibbey said.

However, Kibbey said just locking people up isn’t the answer, and while Clark County is fortunate to have a supportive judicial system, there are still not enough treatment centers.

Kibbey said there needs to be more long-term treatment options such as 6-month or 12-month programs as well as helping folks who may not have insurance.

“We’re gonna see a lot of people lose their insurance and when people lose their insurance it means they lose options for treatment,” he said.

Kibbey receives phone calls every week from citizens looking for treatment options for themselves, friends or family members.

And unfortunately, without insurance, the options are severely limited, he said.

“It takes a village.”

Over the past few years, community efforts in Clark County have more than doubled.

Long-standing organizations are stepping up, new organizations are pitching in, and the entire community is learning.

“Those are all people within our community who are not putting their head in the sand,” Kibbey said. “This is a serious, serious issue, and we have to deal with it. There’s no magic wand, but if we all continue to work together as partners doing what we can where we can, then we can at least, hopefully, make a dent.”

The first step for Clark County to battle the opioid crisis is education, Kibbey said.

“Education, education, education,” he said. “That’s what it always comes down to. That’s how you change stereotypes; that’s how you do away with stigma is by helping people understand what the problem is and what we’re trying to do.”

There are many moving parts, Kibbey said. There are underlying mental health issues, homelessness, and much more the community is striving to understand so Clark County can continue working together to curb the epidemic, he said.

“It takes a village to deal with any kind of a community problem like this and we have to work together,” he said. “We have to work together.”

ASAP is one of the longest-standing community organizations actively working to curb the overdose mortality rate. The board was established in 2004 and include members of local civic groups, school system, law enforcement, health department, family resource centers, treatment facilities, community leaders, drug court coordinators and concerned citizens.

There are self-help groups available every day of the week in Clark County for residents struggling with addiction. Addicts can attend an Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous or a Faith-Based 12-Step Recovery Program.

Some addicts find their way into the court system, and while incarceration removes individuals from their drug-abusing lifestyles for a period, addicts who don’t receive treatment often return to the same cycle of drug use and criminal activity, Kibbey said.

Drug Court attempts to help combat those problems through a supervised program that combines a treatment component with the legal weight of law enforcement. There’s even the needle exchange program and Clark County Drug Disposal Program.

The Achieving Recovery Together (ART) Center is the newest community effort aimed at helping addicts recover and preventing overdoses. ART was formed this year by two women who are recovering addicts – JuaNita Everman and Amber Fields.

Fields said another critical aspect of overdose prevention is breaking the stigma related to drug addiction.

“Addicts aren’t people who deserve to die,” she said. “These are our citizens. Addiction doesn’t discriminate. All different ages, all different socioeconomic levels, all professions, all different people. Our goal is to educate people on addiction and advocate for those in recovery and wanting to be in recovery.”

Fields said it’s also imperative to support people in long-term recovery and try to get them to give their testimony.

“By sharing our stories hopefully our citizens will realize that recovery Is possible,” she said. “We can maintain our sobriety and become successful members of our community.”

“We cannot afford to give up.”

Kibbey uses a story about a starfish as a metaphor for the work local agencies do.

“Once upon a time, there was a man walking on the beach after a big storm had passed. Starfish were scattered across the beach as far as the eye could see, stretching in both directions.

“A boy on the beach was picking up starfish after starfish and throwing them back to the sea.

“Why?” the man asked

“Because they will die up here,” the boy replied.

“You can’t save them all. It doesn’t make any difference.”

“It makes a difference to the ones I put back in the water,” the boy said.”

Kibbey admitts ASAP and the community can’t fix everything. There’s no definitive solution.

But the community can save one starfish, one person, and keep going from there.

“But I know we can make a difference in some people’s lives, and I am personally committed to continue to do whatever I can to help people get their life back,” he said.

When Kibbey worked with a substance abuse group a few years ago, a new member joined and shared his story.

The new member had just returned from his 12th trip to rehab.

“Some people can go through one, and they do fine, but for some people, it takes more,” Kibbey said.

Some people would give up, he said.

Some people would give up trying to curb the opioid epidemic, but not Kibbey and neither has the community as more and more resources and organizations are joining the effort.

And although he has worked with ASAP for 14 years, watching the overdose mortality rate rise and working against the tide, Kibbey remains hopeful, optimistic even.

“We cannot give up,” Kibbey said. “We cannot afford to give up on anybody. We’re talking human beings. We’re talking somebody sons, somebody’s daughters, somebody’s mother, father, child.”