Black history in Clark County is deep and enduring

Published 5:49 pm Thursday, February 25, 2021

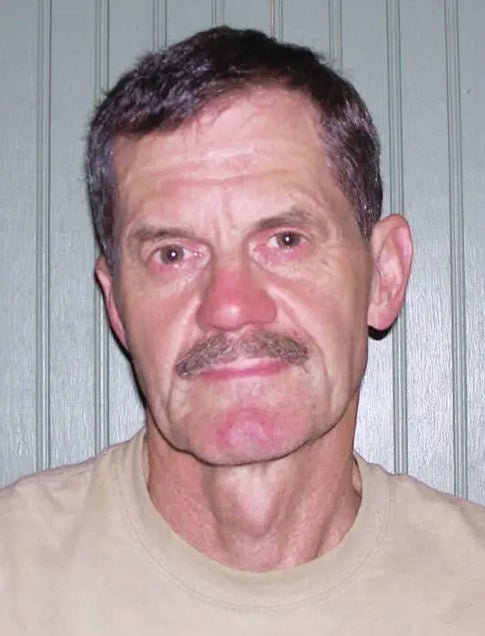

- Pete Koutoulas

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BY PETE KOUTOULAS

Sun Columnist

As Black History Month winds down, I’m reminded of a couple of columns I wrote last February about my tour of Winchester’s African-American Heritage Trail.

I learned so much about the rich history of African Americans in Clark County through the years. I’d like to recount a few highlights of what I learned and wrote about last February.

Just before the Civil War, about 5,000 enslaved people — some 40% of the population — lived in Clark County. There were “slave auctions” right here in our county.

Imagine that — human beings being bought and sold like cattle.

During the post-Civil War “Jim Crow” era, most American cities — including Winchester — had segregated schools, churches, businesses and recreation areas. In Winchester’s thriving Main Street business district, blacks were not welcome.

As a result of segregation, there was a flourishing Black business district along West Washington Street. Known as Poynterville, the area was home to dozens of businesses owned and run by black entrepreneurs. These firms included grocery and retail stores, professional offices, restaurants, schools, pool halls and many more.

Our community has had its share of Black civil rights pioneers such as Jennie Bibbs Didlick and the Rev. Henry Baker. Baker was a pastor, city commissioner, and member of the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame. He helped integrate Winchester’s schools in 1956, and today Baker Intermediate School stands as a tribute to his tenacity.

Before the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court, education in most of America was segregated. This included Clark County.

Some of the schools for “colored children” as they were known, included the Freedmen’s School, Winchester Colored School, and Oliver Street School. There were many colored schools in rural Clark County as well, including three “Rosenwald Schools,” funded by a partnership between the local black community and the Julius Rosenwald charitable fund.

The point of segregated schools, according to their proponents, was to maintain separate facilities for Blacks while maintaining “separate but equal” facilities and resources. Needless to say, the “equal” part of that equation was seldom — if ever — met.

Today in the US, integration is the law. However, in practice, many schools have little or no diversity, reflecting our still too segregated communities. And despite the best efforts of many education professionals, achievement gaps remain. We need to do a better job of educating all children to high standards.

African Americans have participated in every military conflict in our nation’s history. Most of those battles were fought in times when they were separated from their fellow white soldiers and relegated to second-class status.

Black Army regiments were formed in the aftermath of the Civil War primarily to fight native American tribes, who called the units “Buffalo Soldiers.” There were 33 members from Clark County serving in these units.

One member was Jacob Wilks, who also served in the Civil War for the Union. Other locals include John Sidebottom, who served in the Revolutionary War and saved the life of future President James Monroe, and World War II veteran Thomas B. Miller, a member of the famous Tuskeegee Airmen, who went on to be a successful business person in Winchester.

After the Civil War, Black people were pressed to find homes and jobs to sustain their families. Working in service industries and on farms, they founded several communities where they operated their own businesses, churches, schools and cemeteries.

Some of the communities include the aforementioned Poyntersville, Haggardsville, Brunerville, Lisletown and the North Highland Street area, among others.

Three men coached at Oliver Street School and won state championships in multiple sports, including football and boys and girls basketball. They were E.J. Hooper, Hubert Page, and Joe Gilliam, who later went on to coach football at Tennessee State University.

Two of the many outstanding Black athletes to come from Clark County are honored on the trail. They are Robert Brooks and Wilbur Hackett Jr.

Brooks was a multi-sport athlete at Oliver before desegregation allowed him to play at the old Winchester High his senior season. There he led the basketball and football teams to their first winning seasons in many years. Brooks went on to play college and professional football.

Hackett was among the first Black athletes to compete for the University of Kentucky in football. A member of the UK Athletics Hall of Fame, Hackett’s statue now stands at the university’s football stadium.

In the early days of horse racing in Kentucky, most jockeys were Black, and many were natives of Clark County. It is possible that famed African-American jockey Isaac Murphy hailed from Clark County. As documented in a 2020 article in the Sun, some people think the man who won three Kentucky Derbies grew up on a nearby farm.

I’ve learned a lot about my African-American neighbors and their rich history. The Bluegrass Heritage Museum has documented much more of this history. I encourage you to visit the museum and check out their website, including a whole section on Black history.