WHERE IN THE WORLD? Gone But Not Forgotten: Union Depot

Published 11:16 am Friday, January 7, 2022

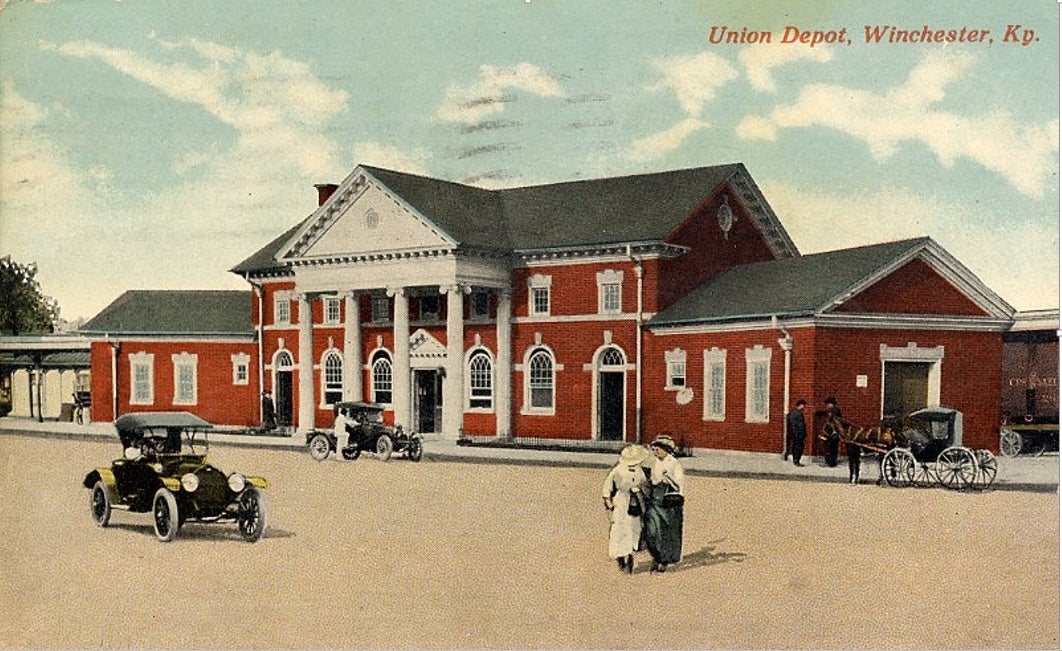

- Erected in 1906, the Union Depot was one of the Winchester's crown jewels for many years. During the early 1900s Winchester counted twenty-two passenger trains daily plus a number of freight trains. (Clark County Public Library Postcard Collection)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

For the older generation in Winchester, July 25, 1981, is a date that will forever live in infamy. On that day the Union Depot was destroyed without notice which “came as a complete surprise to citizens and officials alike.”

The front-page story in the Winchester Sun reported that “an L&N crew, beginning before daylight on a foggy Saturday morning, leveled the building.

Passenger trains had stopped running past the station in 1971 and the building had fallen into disrepair. But the community had been in discussions with the railroad and was nearing an agreement to purchase the building.

Mayor Carroll Ecton had spoken with an L&N superintendent who said, “We’ll give it to you.”

The mayor replied that the city would pay a dollar to make it legal. Bulldozers “plowed into the building minutes before a developer called Winchester city officials to say he was ready to close a deal to convert the old depot on Depot Street to a restaurant.”

By the turn of the 20th century, railroads had made Winchester an important commercial center. Three rail lines passed through the city—Louisville & Nashville, Chesapeake & Ohio, and Lexington & Eastern (later purchased by the L&N). In the early 1900s Winchester counted twenty-two passenger trains daily plus a number of freight trains.

The city always had an edgy relationship with the officious railroad companies.

Mayor John E. Garner took them to task for failing to repair or replace the run-down depot shared by the L&N and C&O which had been built in 1882.

At a Commercial Club banquet, the feisty Garner railed, “It is disappointing that there is no railroad official here tonight to renew his annual promise to build a new depot; not that we would have taken it seriously, of course. They promised our grandfathers, our fathers, us, and doubtless will promise our children.” He said that when one promise expired, “they always…made us another just as good.”

As Garner explained, “The C&O and L&N depot with its surroundings is a mortification to every citizen in town. It is a shame that we are compelled to be humiliated, inconvenienced and nauseated by it. It is lacking in design, size and cleanliness.”

The railroads finally came through in 1905, announcing plans to spend $16,000 to erect a new passenger station. Union Depot opened the following year to much acclaim.

The Lexington Herald reported, “It is in the beautiful colonial style, contains large waiting rooms and offices, every modern comfort and convenience, is steam heated and is approached from all sides by concrete platforms and covered ways.”

The Depot had a classical Georgian Revival design. According to the Kentucky Heritage Commission, the station was “one of the richest and most authentic in detail in addition to being the earliest of its type in Kentucky.”

Over the years the Depot has been the scene of many memorable events. Those most often mentioned are two movies that

used the Depot as a backdrop—The Flim-Flam Man (1967) and Black Beauty (1977)—and the whistle-stop by Harry Truman during his run for president in 1948.

Several other presidents have passed through Winchester on the train. William Howard Taft made a campaign speech from a

specially-built platform at the new Depot during his 1908 campaign. Teddy Roosevelt spoke to a crowd of 2,000 at the Depot in 1912. Woodrow

Wilson’s special train stopped at the station for five minutes in 1916, and Wilson shook hands with some 200 or 300 people. In 1940, 200 persons gathered at the Depot to greet Franklin D. Roosevelt, but the president was fast asleep while his train was shunted from the L&N to the C&O line.

Community reaction to the L&N razing the station was harsh. A Sun editorial declared, “A pile of rubble. That’s all that remains of the old C&O and L&N Depot.

Demolition crews—with no advance notice to the public—moved into position in the early hours of Saturday morning, and in

blitzkreig style had reduced one of the community’s most historic landmarks into a pile of nothingness.”

The following Thursday a funeral was held for the Depot. A casket riding on an old Railway Express wagon was pulled up Main Street from the courthouse to Depot Street, led by city officials and followed by some 200 citizens.

City Commissioner Rev. Henry Baker read a resolution “condemning a most cowardly and deceitful act when agents of the L&N and C&O Railroad snuck into our community like a thief in the night and robbed the city of one of its crown jewels.”

A spokesman for the railroad said the Depot had to go so the tracks could be straightened for safety considerations. Locals viewed that claim with a skeptical eye.

The tracks weren’t straightened during the many years when there was heavy traffic on them. And their only future use was as a siding for an occasional switch engine.

As the poet said, “For all sad words of tongue and pen, the saddest are these, ‘It might have been.’”

Local historian Harry Enoch writes these columns so that people may know a little more about the past so that they can understand the present and being able contend with the future.