The Midland Trail and the early days of Kentucky motorways

Published 10:22 am Tuesday, October 18, 2022

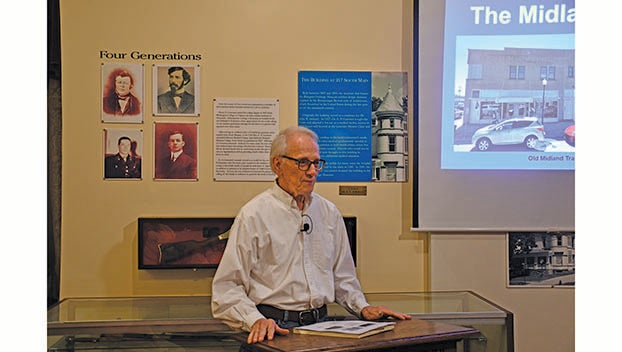

- Local historian Harry Enoch spoke at the Bluegrass Heritage Museum's Second Thursday program about the mystery of the Midland Trail. (Photo by Warren Taylor)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

When he was a young man, local historian Harry Enoch’s grandparents took him to eat at the Midland Trail Hotel in Mount Sterling after church.

One question was always on his mind.

“I would ask people, ‘What was the Midland Trail anyways?’ Nobody knew. There began the mystery,” said Enoch.

His boyhood question spawned a research project that bore fruit in the form of a lecture given during the Bluegrass Heritage Museum’s monthly Second Thursday program last week.

Enoch initially thought that the Midland Trial was a hunting path used by Native Americans and later turned into a frontier road by Kentucky’s earliest pioneers.

However, an internet search revealed the trail’s unlikely origin.

“It is not at all what I expected,” Enoch said. “In 1912, an auto club in Grand Junction, California, laid out a series of connected roads from coast to coast. They picked roads from San Francisco all the way to Colorado and all the way to Washington D.C., and it just so happened that the connected roads went through Kentucky.”

The road system bore a familiar moniker: The Midland Trial.

It was formed in response to the growing popularity of cheaply priced and quality-made automobiles in the early 1900s.

“In 1900, we had had 8,000 automobiles in the whole country. By 12 years later, it was almost one million … The people who had cars wanted to explore,” Enoch said.

Road trips had a fancier name during the early days of the previous century, adventure touring.

Those adventure tourists brave enough to hit the often poorly kept open road faced a problem quite familiar in the modern world, automobile accidents.

“In that year [1912], more than four thousand people died in automobile accidents,” Enoch read from a postcard caption. “It seemed a little shocking to me but given the shape of the roads, not too surprising.”

The Midland Trail Association admitted in a guide that adventure touring could be a chore and was “not altogether a joyous performance,” Enoch read.

The association claimed that any car in good mechanical shape could easily traverse the nation’s nascent motorways but advised motorists to keep a set of tools in case of a calamity.

“This includes a coil of soft iron wire, a good small shovel, an ax, a light rope of steel wire 25 to 50 feet long, a steel pin three feet long in diameter with a sharp point, and steel triple blocks,” Enoch read.

The association also advised motorists to carry a spare tire and at least three tubes.

As the years went by, the association dedicated itself to improving the nation’s roads which had many issues.

“Most of the roads were still unpaved and poorly maintained. In 1913 a statistic said that only seven percent of roads in the U.S. had been paved,” Enoch said. “Then the maps and signage on roads was almost non-existent, which led to lost motorists wandering around trying to find where they were.”

The association began to provide road signs for the trail and convinced the states to form the American Association of State Highway Officials in 1914 to set road design standards.

Soon roads were paved with a mixture of crushed stone and tar.

The Midland Trail entered Kentucky in Louisville and traveled through Lexington, Winchester, and the eastern section of the commonwealth.

The association kept a guide with mile-by-mile details and had good things to say about traveling through Kentucky.

“A tourist on The Midland Trail in Kentucky has open to him a land of endless delight,” Enoch read from the guide.

By 1925 the nation had a joint board on interstate highways, and one of its tasks was to give numbers to American roads.

One of the board’s first undertakings was to develop eight coast-to-coast highways, none of which went through Kentucky.

Gov. William J. Fields rallied the business community around the notion of Kentucky gaining access to such a road. Despite Fields’ protests, the board ignored him.

Kentucky’s Congressional district complained to the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, which ignored that round of protest.

However, it was soon discovered that board members were directing the next coast-to-coast highway through their home states such as Illinois, Missouri, and Oklahoma. The public backlash soon became too great to ignore, and Kentucky got its highway.

The newly christened U.S. 60 ran from Los Angeles to Virginia Beach, and all of it is still in use today across Kentucky. The original route for U.S. 60 went on to become the “Mother Road” U.S. Route 66.

While The Midland Trail might not fall into one’s romantic notion of the past, it is still a significant mile marker in Kentucky transportation history.