Manning the fleet | Recruiting, retaining bus drivers a challenge for school district

Published 8:18 am Saturday, July 22, 2017

- Jim Roarx has driven a school bus for CCPS for about eight years. He says his favorite part of the job is the interaction he has each day with students. (Photo by Seth Littrell)

Jim Roarx wakes up at 4:15 a.m. every day during the school year. He makes himself a cup of coffee and takes his time preparing physically and mentally for a workday full of unpredictable twists and turns — and that’s just driving on the county roads.

Roarx, 67, has been a bus driver for Clark County Public Schools for about eight years. Roarx said he took the job after retiring and looking for something to occupy his time.

The role of a school bus driver came naturally to him, he said, since his wife had worked in CCPS and he loves to interact with children. He also had prior experience driving a church bus.

With eight years of experience, Roarx is considered a long-serving member of the district’s transportation department.

For CCPS and other school districts around the nation, finding a way to recruit and retain bus drivers has been an evergreen issue.

AN ONGOING PROBLEM

“It’s always been an issue, although it seems to be more of an issue now,” CCPS Superintendent Paul Christy said. “They’ve got a tough job with a lot of responsibility on them. The other thing that you’ve got to face at some point is that the pay is not at what it should be.”

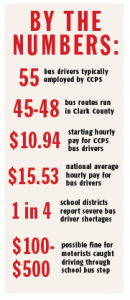

The district has about 55 bus drivers at any given time running between 45 and 48 different routes, with some drivers kept as substitutes and some unassigned.

But while some drivers — like Roarx — keep the job for a long time, the district sees a lot of turnover, Christy said. On average, bus drivers last for three to four years, a number that takes into consideration long-timers and those who quickly leave.

In addition to the early mornings, drivers are also required to work a split shift each work day. Furthermore, drivers in the district are capped at 30 hours, making the job less enticing for people seeking full-time employment.

On the district side of the equation, attendance has also been an issue, according to Operations Director Donald Stump.

“Our board has tried to provide some incentive programs to reduce that, with some success,” Stump said. “Our board adopted a plan several years ago to reinforce new recruits and solicit new recruits. We’ve stepped up our advertisement for vacancies.”

One such recruitment method has been to park buses throughout the community with signs on them advertising for more drivers.

Christy said the district has worked to increase bus driver pay in recent years as one means of improving retention.

“We have stepped up those levels of pay at a higher rate than we have even for teachers,” Christy said.

A job posting on the district’s website shows the starting wage range for drivers advertised between $10.94 and $16.19 an hour.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median wage for bus drivers across the nation was $15.35 per hour — $31,920 a year — in 2016.

He said part of the challenge for school districts is keeping the bus drivers they do hire from leaving for other transportation jobs.

CCPS, like many other districts, pays to send new hires to get the training and testing they need for their Commercial Driver’s License (CDL). However, Christy said it is not uncommon for new hires to leave for better-paying transportation jobs once they have their licenses.

“Once we pay for these people to get their CDLs they’re marketable to Lextran and other companies and other districts,” Stump said.

Roarx said he has seen instances of this happening in his time driving for the district.

“There’s a lot of jobs that require a CDL and they’re all constantly hiring,” he said.

In addition to potentially offering better pay to drivers, these jobs often offer less stressful work environments.

Roarx said he does not find his job difficult, but it does require a particular set of skills.

“You have to be able to multi-task,” Roarx said. “You also have to ask yourself if you can handle 50 kids by yourself.”

The shortage of drivers is not unique to Clark County either. According to Schoolbusfleet.com, an information service for the trade magazine School Bus Fleet Magazine, nearly one in four of 50 districts across the nation polled reported they were facing a severe driver shortage. More than half reported at least a moderate shortage.

To remedy the issue, these districts reported taking some similar steps to CCPS, including raising wages and spending more on advertising. About one third of the districts reported utilizing signup and referral bonuses.

MANAGING STUDENTS AND PARENTS

Roarx said for some people who are hired as bus drivers, the training and testing to drive a large commercial vehicle is not the part of the job that they are unprepared for. Rather, its operating their bus alone while it is full of students.

“Bus drivers are the only classified employees in the district that have the responsibility of supervising students,” Christy said.

In most cases, Clark County bus drivers are the only adults in their bus once it’s loaded with students, so when they are driving they also have to be watching to ensure the proper safety practices are being followed.

“It can be very hard for the little ones to stay in their seats,” Roarx said. “The buses don’t have seat belts but are designed to be safe for children when they’re sitting in them.”

While some school districts are able to put two adults on a bus to help keep order, Roarx said such a move would be financially impossible for a district the size of CCPS. Therefore, the drivers are trained and expected to be able to handle anything that happens on the bus themselves.

The issues differ as the students get older as well, he added. As the students age, they are more likely to have altercations with each other. Sometimes the conflicts require drivers to pull their buses over to handle in person, delaying the bus along its route.

“You learn pretty quick who you have to keep an eye on, and I make those kids sit up front directly behind me,” he said.

Students aren’t the only ones who can give drivers a hard time, either. Sometimes they have to deal with upset parents as well during drop offs or pick ups.

Sources of aggravation can include the bus being behind schedule, or concerns about an incident involving their child while on the bus.

Roarx said most of the time parents are just looking to hear from an adult who witnessed something and may be a bit more objective recalling an incident. But in the event of an incident involving a parent, drivers do have precautions they use.

Christy said all school buses in the district are equipped with security cameras. The district manages the recordings under strict state guidelines, but the drivers have access to a button that they can push to timestamp the recordings if they think something is happening that will need to be reviewed by administrators later.

Stump said the videos are often reviewed upon the request of the bus driver.

HAZARDS ON THE ROAD

But sometimes the biggest hazard for bus drivers is what is going on outside of the vehicle. Roarx said it is common for other motorists to not stop for the buses when they are picking up or dropping off students.

“It happens to at least one bus every day,” Roarx said.

According to state law KRS 189.370, drivers on both sides of any road with fewer than four lanes must come to a complete stop for buses whenever their red lights are flashing and the sign is out.

If drivers are caught passing a stopped bus, they are subject to a fine ranging between $100 and $200 and could face 30 to 60 days in jail.

For subsequent offenses within three years of each other, a motorist can face a fine of $300 to $500 and 60 days to six months in jail.

However, there is little that a bus driver can do to stop a motorist in that moment.

Roarx said the problem has led to many scares throughout his career, especially with the unpredictable nature of children.

“If a kid is holding a piece of paper or something and it gets picked up by the wind and blown into the street, they may very well run after it,” he said.

Roarx added that often when drivers pass the bus it is because they think they know which direction the children will be approaching from, but don’t take into account that students could be approaching from multiple directions.

“Respect the lights,” Roarx said.

NOT A BAD JOB

But with all the issues Roarx has to deal with during the school year, he said he still enjoys his job very much.

“My favorite part is getting to interact with the kids,” he said.

Roarx said the job is a good one for retirees who are looking for some extra work, but he added there’s also a place for young people.

“We have some young moms whose children are students and they are very good drivers,” he said. “It’s a good job for someone who is looking for an extra job but has a limited schedule.”

Christy said there is a behavioral component to having good bus drivers who drive for a long time. He said that when students begin their day with a bus driver they know and trust, their behavior improves. That improvement carries on throughout the school day as well.

“It’s a tough job,” Christy said. “It’s the first person that the kids see in the morning and it’s the last person from the school system many of them see in the afternoon.”